This week our wonderful Gail has allowed me access to her excellent personal blogs, and I’ve selected something which I found really interesting. I’ve never served on a jury (apparently serving H. M Customs & Excise officers were excused by virtue of their commission), but Gail has. Useful information for those wanting to write a convincing courtroom scene.

Doing jury service is part of good citizenship in my opinion, so if you are able to do your bit, then please do. But here are some things that you won’t necessarily be told about doing jury service.

The process starts with you receiving a letter to say you’re wanted to report to court. This should give you a date and time, and everything else you need to know about the practicalities of what you do when reporting for jury service. The first thing you need to do is let your employer know that you have been called. I think you can delay service if you absolutely have to, but you have to come to an agreement with the courts on that and it’s not a process I know anything about. I also believe if you are self employed and can’t afford to take time off, there’s leeway for that too. If for whatever reason you can’t do the service, you do need to talk to your local court about it. Just not turning up is not a good idea, I think it might actually be an offense.

Once sorted, the first day of service arrives and you go to the court, you go to the jury room, get checked in and then you discover the secret of doing jury service. IT IS BORING! Mostly it’s boring because you’re unlikely to get called to serve on a jury immediately. There could be hours, or even days, of just sitting around waiting for that call. Take a book. If you’re a fast reader, take two. Also be aware that being called to do jury service doesn’t mean that you will definitely serve on a jury.

If you actually get called to serve on a jury, be aware that more people are called in than are needed. This is so that the courts can weed out anyone who knows anyone involved in a case. As you tend to serve at your local court, there’s a reasonable chance that at least one of the potential jurors called will know someone in the case. I have to be honest, this was one of the most interesting parts of the whole experience when I did jury service. The only issue that might have arisen for me is that I know a few police officers, but thankfully, none of them were involved in the case I was on.

If you don’t get selected, it’s back to the waiting room, I’m afraid. Good reading time though.

If you get through that selection, then great, you’re on a jury. Don’t be that impressed. Court hearings in real life aren’t like those in films or what you see on TV. They aren’t even like Judge Rinder. There is a lot of slow, steady confirmation of who everyone is. Then there is the questioning for information, and the counter questioning. It’s not surprising that witnesses get confused with the way that lawyers can ask questions, if they do. There was hardly any of that in the case I sat through. It was very pedestrian. Facts were relatively simple. There was one witness, the key witness, who did get a bit of this, but given what he had to say, there was no need of badgering or bothering from the barristers. You may even sit in the jury and wonder why the barristers aren’t asking what you think are obvious questions. There is a good chance that the barristers have thought of those questions too, but also thought the answers wouldn’t support their cases well enough to bother asking them.

Should you find yourself on an interesting case (what constitutes interesting is up to you), then you might also find yourself faced with some evidence that you find disturbing. You may need to brace for that. I have heard of people so upset by what they saw with as a juror that they need counseling. Thankfully, I wasn’t on a case like that.

Eventually – and it can feel like a lifetime even if it’s only a few hours – you get to deliberate as a jury. It’s one of those moments in life when you realise that common sense isn’t as common as you might like. People weren’t necessarily listening to what was actually said. It’s also when you get to see the CSI Effect in full force. Better explanations are available elsewhere, so if you’re going to use this phenomenon in a book, please research it more thoroughly, but basically it’s where what people have seen on TV/read in books overtakes reality. Jurors want to do the investigating for the case. They might ask for evidence that wasn’t provided in the case (which they won’t get). They want to see the forensic evidence as ultimate proof, when in many cases (not all), it’s just an indication of presence/proximity.

Now, I don’t know a lot of people who have done jury service. You don’t exactly get to bond with your fellow juror. There again, I’m not the easy bonding type. Maybe others do. My point is, I don’t know anyone who has returned a guilty verdict. Obviously, people do, but not the ones I know. Now one of these was because they believed the accused was, in fact, not guilty. However, for me, and a couple of others, we were all pretty sure that the accused was guilty, but the barrister for the prosecution simply didn’t or couldn’t prove it. So we had no choice but to return a not guilty verdict. That worries me. I do to think that we have in the UK one of the best legal systems going, but my experience makes me wonder how often the guilty get off. Not to mention, how often the innocent get found guilty. There is no perfect system that can guarantee 100% that the verdict will be the ‘right’ one. Whatever else you might think from what’s written above, you should know that I am 100% behind the trial by jury system and would not advocate changing it for all it’s flaws.

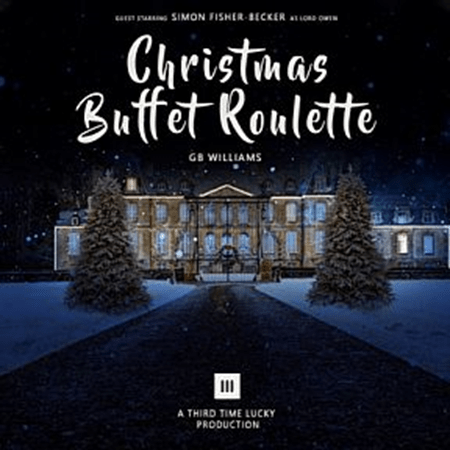

GB Williams specialises in complex, fast-paced crime novels, such as the Locked Triology. GB was shortlisted for the 2014 CWA Margery Allingham Short Story Competition with the story Last Shakes, now available in Last Cut Casebook. As well as crime, she also writes steampunk and horror

You can read more about G B Williams on her website here