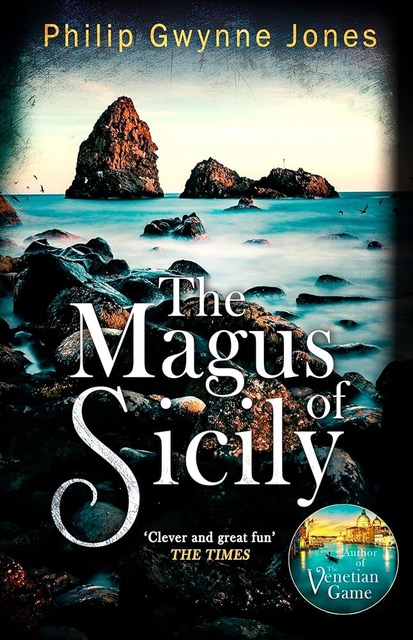

The Magus of Sicily: Philip Gwynne Jones

“Nathan will be back, won’t he?”

“There will be another Venice novel, won’t there?”

I’ve had a lot of messages like this recently. The reason? Well, after eight novels, my protagonist Nathan Sutherland – British Honorary Consul in Venice and occasional crime fighter – is taking a well-deserved break.

I’m not bored with him or with Venice at all. No, time in his company – along with Dario, Fede, Gramsci and the others – is time well spent. But after a decade – I started writing “The Venetian Game” at the end of 2014 – I decided the two of us needed a short break.

And so, for this year at least, the action shifts to Sicily and two new protagonists, Nedda Leonardi and Calogero Maugeri. Things are just a little different this time – third person POV for one thing (I almost bottled it at one stage and went back to the comfort of the first person, but – thankfully – I couldn’t make it work and so I persevered). More importantly, there are actual Italian protagonists – after more than a decade in the country, I felt I was just about ready to write what I hope are convincing centre-stage Italian characters.

Why Sicily? Well, it’s the part of Italy, other than Venice, that we know best. And the island, roughly the size of Wales, is just a story-generating machine. Rich in history, literature, art and archaeology; a land existing under a volcano, a melting-pot of East meets West and home to some of the most stunning landscapes (oh and, of course, food) in Europe – it simply needed to be done.

Sicily, I hope, will keep Venice fresh; and vice-versa. At the moment, I’m writing next year’s Nathan novel and enjoying getting into his head again. But I tell you what, part of me also wants to be back in Sicily with Nedda and Calogero. And I think that’s a good thing.

“The Magus of Sicily” is a book I enjoyed writing. It’s also a book I’m proud of. If you like the Venice books, give it a go – and I wish you happy reading!

Here’s the Prologue for you:-

Perhaps the first thing to learn about Acireale, is what to call

Acireale. Sicilians would call it Jaciriali. Locals would call it

Jaci. Apart from those that call it Aci, of course.

Its origins date back to the fabled Greek city of Xiphonia,

a city so lost to memory that nobody is quite sure where it was

or even if it ever existed. And so, the reasoning goes, it might

as well have been here as anywhere else.

The shepherd boy Acis, they say, fell in love with the

nymph Galatea. This had the unfortunate effect of angering

his love rival, the cyclops Polyphemus. In terms of a con-

test, shepherd boy versus cyclops was always likely to be an

un equal one, and Acis was unceremoniously squashed under

a boulder, his blood flowing out and becoming the river that

the Greeks called Akis.

Acireale looks out upon the Ionian Sea, and the Ciclopi off

the coast of postcard-pretty Aci Trezza, the Cyclopean Isles

hurled into the sea by the blinded, enraged Polyphemus in his

attempt to kill the fleeing Odysseus. The bay sweeps around

to Aci Castello, dominated by its black basalt fortress, and

all the way to the city of Catania, its baroque centro storico

surrounded by a grubbier, grittier urban sprawl. Catania has

been buried under lava no fewer than seventeen times in its

history, which has bred in its residents a curious mixture of

fatalism and optimism.

Greeks and Romans, Arabs and Normans and Spaniards,

all passed through here and left their mark. Christianity and

Islam, Judaism and ancient folk-myth have roots that lie deep

within its soil.

Acireale rebuilt itself following the great earthquake of

1693. It raised the Italian Tricolour for the first time in 1860,

as part of Garibaldi’s ‘Expedition of a Thousand’. In the twen-

tieth century it survived Mussolini’s fascism, Allied bombing

and the best efforts of the Cosa Nostra. Still it remains, opti-

mistically clinging to the lower slopes of Mount Etna.

A land and a city with deep roots, a troubled past and an

uncertain future, Acireale lies there, under the volcano, hewn

from the lava and wedded to the sea.

A land with a violent past and, occasionally, a violent

present as well. . .